"He had been before in drawing rooms hung with red damask, with pictures 'of the Italian school'; what struck him was the way in which Medora Manson's shabby hired house, with its blightened background of pampas grass and Rogers statuettes, had, by a turn of the hand, and the skillful use of a few properties, been transformed into something intimate, 'foreign', subtly suggestive of old romantic scenes and sentiments. He tried to analyse the trick, to find a clue to it in the way the chairs and tables were grouped, in the fact that only two Jacqueminot roses (of which nobody ever bought less than a dozen) had been placed in the slender vase at his elbow, and in the vague pervading perfume that was not what one put on handkerchiefs, but rather like the scent of some far-off bazaar, a smell made up of Turkish coffee and ambergris and dried roses."

~Edith Wharton, The Age of Innocence

I have been re-reading Wharton's masterpiece and noticing page after page the meticulous care with which the author has created a vivid universe of that crumbling world of social conventions. I follow the eyes and thoughts of late 19th century young gentleman Newland Archer, about to marry the perfect girl of his New York circle, May Welland, but who nevertheless ~out of a rebellion of his inquisitive spirit~ ends up in a frustrated, unfulfilled love story with her cousin, the Countess Olenska; a woman who inwardly snubs conventions, but seems eternally trapped by them in a pre-arranged world of genteel suffocation. No detail has been spared by the author in delineating the mores, the customs, the rites and rituals of a disappearing world and, within it all, one of the most characteristic seems to be the one hinting at smells; such as the above passage, recounting the house in which the Countess Olenska stays, a house she has decorated herself and which reflects her rebellious, cosmopolitan and free nature.

Other fragrant details surface frequently too: May Welland receives posies of lilies of the valley daily ~ Diana-like, pure, beautiful, virginal and above board~ all through her engagement to Newland. As he shops for her bouquet he suddenly notices...

..."a cluster of yellow roses. He had never seen any as sun-golden before and his first impulse was to send them to May instead of the lilies. But they did not look like her -there was something too rich, too strong, in their fiery beauty. In a sudden revulsion of mood, and almost without knowing what he did, he signed to the florist to lay the roses in another long box, and slipped his card into a second envelope, on which he wrote the name of the Countess Olenska; then, just as he was turning away, he drew the card out again, and left the empty envelope on the box".

Such small details can create a whole scene! The lily of the valley stands as the symbol of the virgin bride who is spotless and seems frail, yet surfaces triumphant in the conventional approach to marriage she seeks in the end, much like the aroma of the tiny blossom is piercingly sweet and surpasses most others. The sun-yellow rose is more mature, more feminine in a retro, "full" way, symbolising the giving and open nature of Ellen Olenska, its delicate scent a crumbling beauty that is trampled by those whose trail travels farthest.

Perfume mentions in novels, whether by general description or by specific brand names is not new, but it always strikes me as poignant and significant in setting the mood and tone of the literary work at hand. Indeed, there are books in which it sets the very plot, like obvious paradigm

Das Parfum by Patrick S

üskind,

À Rebours (

Against the Grain) by J.K. Huysmans or

Jitterbug Perfume by Tom Robbins. Then, they are those which use perfume references creatively, like

The Petty Demon (Melkiy Bes) by Fyodor Sologub, chronicling Peredonov's ambition to rise from instructor to rural gymnasium to school inspector as well as the erotic dalliance between Sasha Pulnivok and Lyudmilla Rutilova.

Take

White Oleander by Janet Finch as well, where every character signals a hidden side of them by their choice of fragrance: The biological mom looks stealthy if deliquent, but smells of shy, tender

violets. The foster mom with the suicidal tendencies chooses

L'Air du Temps, fusing her frail personality with the graceful and assured arc of the Nina Ricci's classic. The upscale hooker down the road wears steely and classy chypre

Ma Griffe by Carven. Even the fragrant gift of the promiscuous neighbour to the girl heroine, Penhaligon's

Love Potion No.9, is a plea and realisation for what the protagonist needs most: approval.

In Nancy Mitford's

The Pursuit of Love the protagonist's wearing of

Guerlain's classic

Après l'Ondée elicits favourable reception. In

Joanne Harris's Chocolat the depiction of all the village women wearing

Chanel No.5, till the arrival of the trail blaizer heroine, is akin to a red flag of conventions-adoring set to be shred to pieces. In Dodie Smith's

I Capture the Castle the scent that permeates the romantic atmosphere is Penhaligon's

Bluebell; as British as you can get.

Sometimes scent in novels can even become an idée fixe:

"...and I could see Maxim standing at the foot of the stairs, laughing, shaking hands, turning to someone who stood by his side, tall and slim, with dark hair, said the bishop's wife, dark hair against a white face, someone whose quick eyes saw to the comfort of her guests, who gave an order over her shoulder to a servant, someone who was never awkward, never without grace, who when she danced left a stab of perfume in the air like a white azalea."

Thus writes

Daphne du Maurier in Rebecca and continues:

"And then I knew that the vanished scent upon the handkerchief was the same as the crushed white petals of the azaleas in the Happy Valley." Or "The wardrobe smelt stuffy, queer. The azalea scent, so fragrant and delicate in the air, had turned stale in the wardrobe, tarnishing the silver dresses and the brocade, and the breath of it wafted toward me now from the open doors, faded and old."

And who can forget literary giant Honoré de Balzac when he describes down to the filthy detail and to the last minutiae the places where his heroes live and work in

Père Goriot?

Fragrance references and scented descriptions add a whole different sublayer to a novel's charm and sometimes worth, by injecting it with a subtle nuance like nothing else. Simply put, the novel would be incomplete without referring that sense which makes up for so many of our memories, sentiments, preconceptions and aversions.

What about you?

Do you enjoy fragrance references in novels or do they distract you? And which are your favourites? Share them in the comments.

The resinous depths of its core, a complex and satisfyingly rich amber accord, recall the play between light and darkness in the paintings of the Spanish masters; dramatic expanses of vivid motion, shadowy corners that hide small details with significance that doesn't pass unnoticed. The double whammy of a misleading name and the wrong company (few houses are more derisive!) just conspired it to make it a very under the radar fragrance. Which is exactly why I decided to get the scalpel and start surgery on this page.

The resinous depths of its core, a complex and satisfyingly rich amber accord, recall the play between light and darkness in the paintings of the Spanish masters; dramatic expanses of vivid motion, shadowy corners that hide small details with significance that doesn't pass unnoticed. The double whammy of a misleading name and the wrong company (few houses are more derisive!) just conspired it to make it a very under the radar fragrance. Which is exactly why I decided to get the scalpel and start surgery on this page..jpg)

De-Stress – Blended from frankincense, lavender, ylang ylang and german chamomile, the #11 De-Stress blend helps to steady nerves, reduce tension and reduce stress on the limbic system. The oils in this blend are effective in countering situational irritation and angst and promote emotional flexibility. De-Stress helps you to stay cool under fire, encouraging graciousness and diplomacy, balance and decisiveness.

De-Stress – Blended from frankincense, lavender, ylang ylang and german chamomile, the #11 De-Stress blend helps to steady nerves, reduce tension and reduce stress on the limbic system. The oils in this blend are effective in countering situational irritation and angst and promote emotional flexibility. De-Stress helps you to stay cool under fire, encouraging graciousness and diplomacy, balance and decisiveness. Invigorate – Blended from cedarwood, rosemary, black pepper and juniper, the #01 Invigorate blend helps to stimulate circulation, motivate and energize. These warming oils help oxygenate the blood and promote blood flow, which in turn energizes the body.

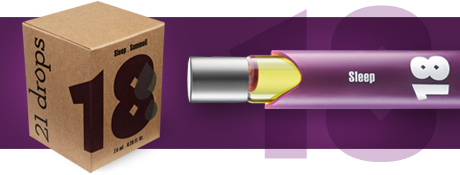

Invigorate – Blended from cedarwood, rosemary, black pepper and juniper, the #01 Invigorate blend helps to stimulate circulation, motivate and energize. These warming oils help oxygenate the blood and promote blood flow, which in turn energizes the body. Sleep – Blended from sandalwood, ylang ylang, palmarosa and vetiver, the #18 Sleep blend helps to sedate, soothe and quiet. The oils in this blend work on the nervous system to hush a racing anxious mind and settle states of restlessness and agitation.

Sleep – Blended from sandalwood, ylang ylang, palmarosa and vetiver, the #18 Sleep blend helps to sedate, soothe and quiet. The oils in this blend work on the nervous system to hush a racing anxious mind and settle states of restlessness and agitation.