After the Big Bruisers of the 80s, so ingrained into the decade of decadence and carnality, leather scents took a back seat until the modern fragrance niche phenomenon erupted like a well-oiled explosive mechanism, issuing forgotten ripples into the stagnant pond of ozonic-marines of the early 90s. Suddenly those “weird” smells were cool again!

After the Big Bruisers of the 80s, so ingrained into the decade of decadence and carnality, leather scents took a back seat until the modern fragrance niche phenomenon erupted like a well-oiled explosive mechanism, issuing forgotten ripples into the stagnant pond of ozonic-marines of the early 90s. Suddenly those “weird” smells were cool again!Modern leather scents are divided in so many categories it was a Herculean feat trying to sort them out. There is a leather fragrance for every mood these days.

So this little list is meant to help you navigate your way through the plethora on offer, but it's by no means a definitive guide: that would implicate your own nose.

*The Orientalised Leathers

When leathers take a turn for the Middle East or the exotic spices and dried fruits caravan.

Cuir Mauresque by Serge Lutens: a Moorish scent (therefore of Spanish Leather tradition), it infuses cuir with clove, mandarin rind and aloeswood to turn the smoky heart of Tabac Blond into a modern, sweeter alternative with a little funk.

Cuir Ottoman by Parfums d’Empire: described by a dear friend as “feeling like actually wearing a leather couch” it is uber-luxe, very warm and opulent.

Ambre Russe by Parfums d’Empire: the hangover-ed sister of Cuir Ottoman who drinks dark Russian tea to perk her up.

Cuir Ambré No.3 by Prada: unisex leather with an orientalised twist.

Montale Oud Cuir D'Arabie: intensely leathery with the characteristic mustiness of aromatic oud. For those who go for the potently woody.

Fleur de Peau by Keiko Mecheri: heavy heliotrope over smooth nubbuck, bittersweet, a little soapy, for those who like Daim Blond and can abide sweet leathers.

Parfum d’Habit by Maître Parfumeur et Gantier: lush, with a delectable fruity top married with the rosiness of geranium and patcouli.

*The Quirky Leathers

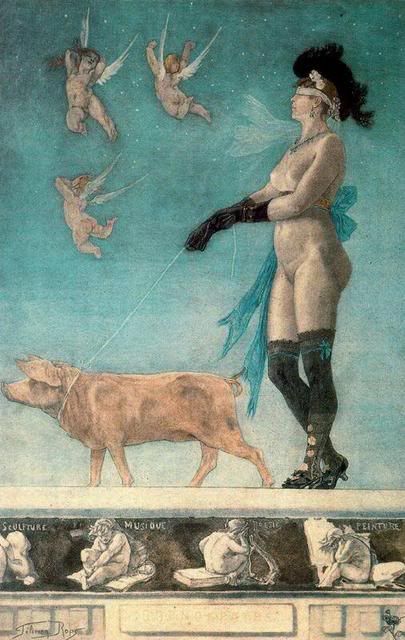

Some leather fragrances do not want to conform, like spoiled brats who want to do their own thing. Sometimes this is a good thing!

Dzing! by L’artisan: the hide of a living animal, completely weird and therefore compelling. Warm and nuzzling, to some it might even smell like zoo dung, but it might bring out your inner "Cat People"

Black by Bvlgari: rubbery, fetishist and urban. Close to Dzing!, with a more vanillic underlay.

Baladin by De Nicolai: vetiver-smeared leather and you know there is something sophisticated hidding here.

Jean-Luc Amsler Prive Homme: leather nappa stretched on a rock (a mineral touch)

Marquis de Sade by Histoire des Parfums: stewed prunes kept in a leather pouch for consuming au lit, après.

Marquis de Sade by Histoire des Parfums: stewed prunes kept in a leather pouch for consuming au lit, après.Rose d’Homme by Rosine: or how a rose can smell as sweet by no other name. A bastard who makes you look twice and wins you in the end. For rose-haters.

Idole by Lubin: boozy like a drunken pirate in the Caribbean

Nuit Noire by Mona di Orio: citrus and floral avalanche (orange blossom and tuberose) over an animalic musky and civet-catty note that recalls visions of Lutens at his best.

Corps et Ames by Parfumerie Generale: with a fierce chyprish quality about it, wonderfully unique

*The Butch Leathers

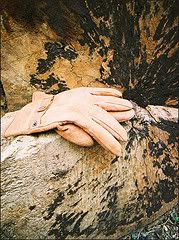

Because some days you want to get out into cow country and never look back.

Lonestar Memories by Andy Tauer: an outdoor smell of leather chaps on someone who has been cooking over a woodfire on a campsite for hours on end. It grabs you and never lets go.

Cuiron by Helmut Lang: an intense slap of leather from an austere designer glove and an invitation to a modern duel

Patchouli 24 by Le Labo: full of birch tar, no patchouli, what a misleading name!

*The Subtle Whisper Leathers

Sometimes there only needs to be a passing whiff...

No.19 by Chanel: the toughness under the white shirt and the powdery iris is the winning combination of elegance

Kelly Calèche by Hermès: “soles of angel leather” indeed! The prettiest introduction to proper perfumes for a young woman. Quality all the way. A sleeper classic!

Fleur de Narcisse by L’artisan: unattainably heavenly like the rotting corpse of a soldier on a spring field through the eyes of Rimbaud

Dzongkha by L’artisan: the temple smells of wood, but the shoes of the pilgrims left outside have their own tale to recount

Tuscan Leather by Tom Ford Private Blend: opulent aroma of burnt wood and cigar smoke of a poser; rather soft for something named Leather

Vie de Chateau by De Nicolai: starts as traditional cologne, graduates to so much more. Aristocratic.

Vie de Chateau by De Nicolai: starts as traditional cologne, graduates to so much more. Aristocratic.John Varvatos pour Homme: Varvatos (pronounced Var-VA-tos) is a designer whose name in Greek refers to a man who smells of pungent and quite intense sex juices ~his own! Unfortunately the onomatopoieia has not been entirely successful: it doesn’t smell as such. What a pity: It would have been the perfect ice-breaker!

VIP room: a very interesting, limited edition by the infamous Parisian club house. Suede-like, less sweet than Daim Blond and ultimately a favourite. Too bad it’s getting hard to find!

Etienne Aigner Suede Edition: light, smooth, soft, with a salty undertone of real suede.

Daim Blond by Serge Lutens: suede with sweet apricots and an almondy powdery note, too sweet sometimes.

Cuir Beluga by Guerlain: the merest hint of leather for budding leatheristas, rather sweet.

Habit Rouge by Guerlain: leather hidding under powder; a well-bred gentleman is having a relaxing day at his club.

Cacharel pour Homme: fine suede, rather too traditionally masculine to make a striking impression any more

Kitsune by Armando Martinez: smooth, musky, suede-like and soft like his other nuzzling scents, with a fabulous name.

Histoire d’Eau by Mauboussin: light summery leather that can be worn anywhere really.

Trussardi Donna: why did they reformulate this one? In its white mock croc bottle it was the loveliest torrid affair of feminine flowers and costly nubbuck. I miss it…

Rykiel Woman-not for men! by Sonia Rykiel: a sexy wink of the eye that comes from musk and leather speaks in silence under the mask of powder and amber. Too well blended for anything to pop out.

Vol de Nuit by Guerlain: an exceptional creation that even features a slight hint of leather if you close your eyes and picture Saint-Exupery in his bomber jacket flying over the Sahara.

Shalimar by Guerlain: the bronze deity

Murasaki by Shiseido: named after the heroine and author of Genji Monogatari (The Tale of Genji)

Read the rest of the Leather Series following these links:

Part 1, Part 2, Part 3, Part 4,

Part 5, Part 6, Part 7, Part 8,

Part 9, Part 10, Part 11

Pic of The Avengers and Quills courtesy of Allposters, pic of Marc Jacobs shoes originally uploaded on BlogdorfGoodman

.jpg)

.jpg)

.bmp)

.jpg)

.jpg)