Hedione or methyl dihydrojasmonate is an aromachemical (patented as Hedione by aroma-producing company Firmenich) that is often used in composition in substitution for jasmine absolute, but also for the sake of its own fresh-citrusy and green tonality.

Hedione lacks the clotted cream density of natural jasmine, recalling much more the living vine in the warmth of summer mornings and for that reason it is considered a beautiful material that offers quite a bit in the production of fine perfumes.

Hedione lacks the clotted cream density of natural jasmine, recalling much more the living vine in the warmth of summer mornings and for that reason it is considered a beautiful material that offers quite a bit in the production of fine perfumes.Perfumer Lyn Harris, nose of the brand Miller Harris and also the independent nose behind many well-known creations not credited to her name, calls it “transparent jasmine” and attributes to it the capacity to give fizz to citrus notes much “like champagne”. (See? it’s not only aldehydes which do that!)

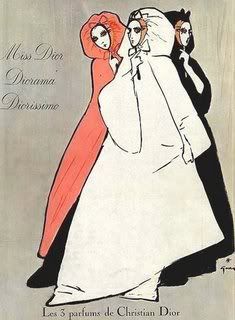

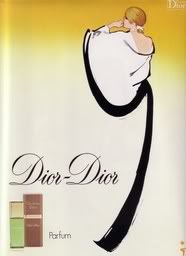

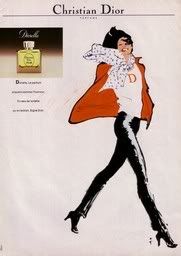

First used in the classic men’s cologne Eau Sauvage, composed by Edmond Roudnitska in 1966, hedione had been isolated from jasmine absolute and went on to revolutionize men’s scents with the inclusion of a green floral note. Eau Sauvage was so successful that many women went on to adopt it as their own personal fragrance leading the house of Dior to the subsequent introduction of Diorella in 1972, composed by the same legendary nose, blending the green floral with hints of peach, honeysuckle, rose and cyclamen in addition to the herbal citrusy notes of the masculine counterpart, all anchored by a base of cool vetiver, patchouli and oakmoss, lending a mysterious, aloof and twilit air to women who went for it.

Ten years after its introduction to perfumery, in 1976, it was the turn of Jean Claude Ellena to coax hedione in a composition that exploited its fresh and lively character to great aplomb in the production of First by jewelry house Van Cleef & Arpels (the name derived from the fact that it was their first fragrant offering, but also the first scent to come out of a jeweler too ~subsequently many followed in its tracks with notable success).

In it, Ellena used 10 times the concentration of hedione used in Eau Sauvage, married to natural jasmine as well as rose de mai (rosa centifollia, which is also a "crystalline" variety), narcissus, orris, ylang ylang and a hint of carnation with the flying trapeze of aldehydes on top and the plush of vetiver, amber and vanilla at the bottom which accounted for a luminous and luxurious floral.

In it, Ellena used 10 times the concentration of hedione used in Eau Sauvage, married to natural jasmine as well as rose de mai (rosa centifollia, which is also a "crystalline" variety), narcissus, orris, ylang ylang and a hint of carnation with the flying trapeze of aldehydes on top and the plush of vetiver, amber and vanilla at the bottom which accounted for a luminous and luxurious floral.Hedione also makes a memorable appearance in many other perfumes, such as the classic Chamade by Guerlain (introduced in 1969), Chanel no.19 (1970) and Must by Cartier (1981) and in many of the modern airy fragrances such as CKone, Blush by Marc Jacobs, the shared scent Paco by Paco Rabanne or ~surprisingly~ in the bombastic Angel by Thierry Mugler, in which it is used as a fresh top note along with helional! Perhaps if you want to feel it used in spades smell L'Eau d'Issey by Issey Miyake: the aquatic/ozonic notes cannot hide its radiance.

Its uses are legion, especially since it acts as a supreme smoothener of the rest of the ingredients. In Terre d'Hermes, perfumer Jean Claude Ellena uses lots of it to bring out the softer side of hesperidic bergamot and to fan out the woodier aspects.

High-cis Hedione is an isomer which gives a jasmine tea profile (not surprisingly, as the component naturally occurs in tea), more diffusive and less floral and thus useful in masculine blends, but it costs more than regular hedione and poses problems of stability in acidic environments. Some of the Bulgari "tea" scents, such as Bulgari Eau au Thé Rouge and Bulgari Eau au Thé Blanc are good reference points if you want to smell this in action.

Despite hedione's unlikeness to natural jasmine absolute and essential oil (which are much lusher, narcotic and indolic), perfumers have used it to supreme results in the history of fine fragrance of the last 40 years, occassionaly using it up to 35% concentrations, although it's more usual to be featured in ratios of 2-15%.

Related reading on Perfume Shrine: Perfumery Materials, The Jasmine Series

pic of jasmine via Gracemagazine. Bottle of First via zensoaps.com

.jpg)