|

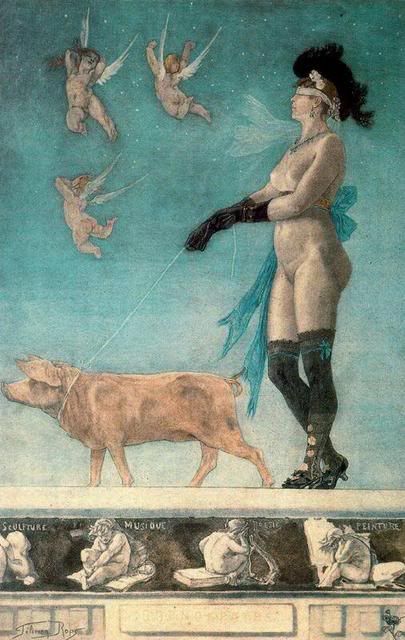

| Dior Poison "memento mori" ad, "all is vanity" |

But it is rare that a perfume company uses images of death to advertise their products; in this case Poison by Christian Dior.

You don't get what I am talking about? Squint. Now look again with your vampire eyes...The image of a skull is looking back at you through the mirror, the bottles and the torso of the woman sitting in front of her dresser. See?

Of course Dali chose to depict it through naked women forming the parts of the skull, which is an allusion to the other half of the equlibrium of Eros and Thanatos. The regeneristic power of sexual desire and copulation is man's only means of transcedenting death. This of course lies at the root of ancient mysteries and rituals, such as the Orphic or Eleusinian Mysteries in ancient Greece.

During the Middle Ages, at a time when general lack of education swerved the emphasis of ecclesiastical catechy into iconography rather than scripture, images of horrible monstrosity became almost normal in the abodes of the holy. One only has to take a look at the gargoyles of late-Gothic churches across Europe to ascertain this. In this environment the notion of Memento Mori flourished; a typically simple depiction of a skull making an appearence somewhere along a painting, a psalm book, or a tapestry.

And how would this culminate in the above Dior Poison advertisement? Simple: the name Poison lends itself to imagery of Thanatos, through its connotations of its meaning and the fairy tale poisoned apple like its bottle shape suggests. Apple, a fruit full of its own connotations of sin and corruption!

Perhaps the advertisers want us to remember that just as their perfume can symbolically be lethal (and in copious amounts I am sure it can be!), it can also put a spin into the other half of the eternal duo: Eros.

.jpg)

.jpg)