by guest writer Denyse Beaulieu

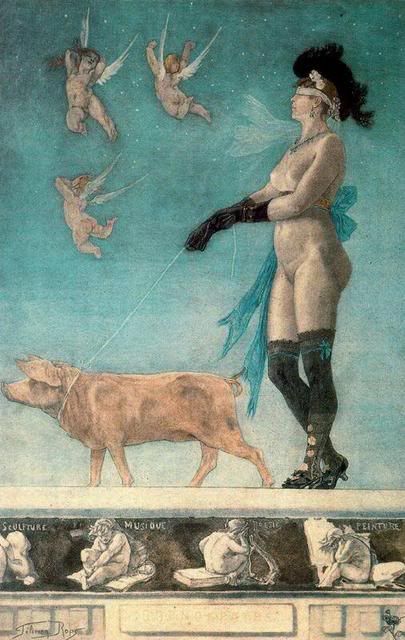

Tabac Blond was the opening salve of the garçonnes’ raid on gentlemen’s dressing tables. Its name evokes the “blonde” tobacco women had just started smoking in public (interestingly, Marlboros were launched as a women’s brand in 1924 with a red filter to mask lipstick traces). The fragrance was purportedly meant to blend with, and cover up, the still-shocking smell of cigarettes: smoking was still thought to be a sign of loose morals.

Despite its name, Tabac Blond is predominantly a leather scent, the first of its family to be composed for women and as such, a small but significant revolution. Though perfumery had recently started to stray from the floral bouquets thought to be the only fragrances suitable for ladies (Coty Chypre was launched in 1917), it had never ventured so far into the non-floral. Granted, there are floral notes, but apart from ylang-ylang, the clove-y piquancy of carnation and the cool powdery metallic note of iris don’t stray much from masculine territory. Amber and musk smooth down the bitter smokiness of the leather/tobacco leaf duet, providing the opulent “roundness” characteristic of classic Carons. And it is this ambery-powdery base – redolent of powdered faces and lipstick traces on perfumed cigarettes – that pulls the gender-crossing Tabac Blond back into feminine territory to the contemporary nose, despite Luca Turin’s calling it “dykey and angular and dark and totally unpresentable” in Chandler Burr’s Emperor of Scent.

.jpg) Like its younger sister Habanita (1921), Tabac Blond’s rich, golden-honeyed, slightly louche sillage speaks of late, smoke-laden nights at the Bal Nègre in the arms of Cuban aristocrats or déclassé Russian émigrés, rather than exhilarating rides in fast cars driven by the new Eves…

Like its younger sister Habanita (1921), Tabac Blond’s rich, golden-honeyed, slightly louche sillage speaks of late, smoke-laden nights at the Bal Nègre in the arms of Cuban aristocrats or déclassé Russian émigrés, rather than exhilarating rides in fast cars driven by the new Eves…Not so Knize Ten, the 1924 fragrance composed by Vincent Roubert (who worked with Coty on L’Or and L’Aimant) for the Viennese tailor Knize. The Knize boutique was famously designed in 1913 by architect Adolf Loos, whose anti-Art Nouveau essay, Ornament and Crime, helped define Modernist aesthetics with its smooth surfaces and pure play on volume. The scent itself was introduced to complement the clothier’s first ready-to-wear men’s line and in its opening notes, it clearly speaks in a masculine tone. The leather, paired with bergamot, petitgrain, orange, lemon and the slightly medicinal rosemary, is as dryly authoritative as a sharply-cut gabardine suit. As it eases into wear, rose, orris and carnation throw in a gender-bending curve ~Marlene Dietrich (herself a Knize patron) may have well slipped into that suit… The leather itself is of that of the wrist-watchband or fine shoe rather than the pungent “cuir de russie” boot. But despite the richly animalic base – musk, amber and castoreum – hinting at bridled desires, Knize Ten retains the buffered, well-bred smoothness of gentleman who never felt the need to set foot in the cigar-smoke laden cabinet of Herr Doktor Freud…

His twin sister Chanel Cuir de Russie (also 1924) clearly departs from the butch Cossack boot and its birch-tar roughness. In fact, in an anecdote told by the composer Ernest Beaux to Chanel’s second perfumer Henri Robert, and transmitted to the third perfumer of the house, Jacques Polge, this particular “cuir” was meant to reproduce the delicate smell of the fine leather pouches wrapping precious jewel – another type of loot, as it were, than what the Cossack bore away on their horses. Cuir de Russie is a tribute to the impact of the Russian émigrés on the intellectual and aesthetic life of 1920s Paris -- Beaux himself, of course, was a Russian exile of French descent and Mademoiselle’s fashion house was peopled with elegant Russian aristocrats hired as sales assistants and models – as well as a radically modernist reworking of a by-then decades-old theme.

But more later in Helg’s review…

Photo by Irving Penn courtesy of ArtPhotoGallery.com, painting by Jack Vettriano Fetish, courtesy of angelarthouse

.jpg)