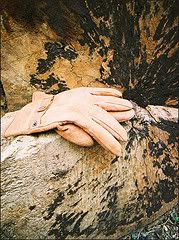

Tanning requires the use of nitrogenous waste to cure hides, to make them fit to be processed for the items the aristocracy requested and to kill bacteria that would infest dead tissue. Even today in places where traditional tanning techniques are used, such as Morocco, there are big basins of human and animal urine and feces, along with various tree barks rich in tannin, where workers have to stand with their feet naked, immersed in this revolting liquid, stretching the shaved hides, making them pliable and soft. The smell is trully insupportable for the wandering tourist and it is not without intense distaste that one has to urgently seek solace in a scented handerkchief or a small bunch of greenery to relieve the nose from the malicious fumes emanating from those ponds of filth.

It was not that dissimilar back during Renaissance times, when treating hides followed this method, the atmosphere of which Atelier Grimal from the “Perfume” coffret by Mugler (based on the novel and movie “Perfume: story of a murderer”) tried to capture.

From Florence and Italy, a stronghold of the European commerce with the East and its aromatic tradition, perfumes came to France through historical personages of the Medici family and through an item of clothing: gloves.

The Gantiers, the Guild of Glovers that is, was one of the most important guilds in France. It was in 1268 that it was granted the status of corporation in Paris. It was later under Colbert’s economic management that the gantiers parfumers were awarded pride of place in the Six Corps; the six most powerful societies of the day. This allowed them to have access to expensive products from overseas. The production of leather goods took place principally in Montpellier, a town famous for its tanneries. It was there that Eau de la Reine de Hongrie (Hungary Water) was produced as well. Another centre for tanneries was Grasse. The two towns were economic rivals.

Catherine de Medici (1519-1589), Queen of France from 1547 to 1559 and mother to three kings, was a personality that hasn’t been reinstated historically-speaking yet. The stigma of murderess is still attached, as she used special mixes to get rid of her enemies and was implicated in the St.Bartholomew’s Night massacre. When she left Italy to marry Henri, Duc d'Orleans, she didn’t leave behind her favourite artists, poets and even her own perfumer, René le Florentin ~named Renato Bianco at birth. It was he who scented the gloves that poisoned Jeanne D’Albert, mother of Henry IV. Catherine also made use of poison rings: jewels that opened to reveal a hollow place that contained poison to be poured into drinks and food. Monstrous as the habit seems to us, it was nonetheless very common in the courts of Europe at the time and Catherine turned it into high art. René was the first perfumer to open shop in Paris and soon anyone who was anyone flocked to his door to purchase his offerings; scented goods and ~discreetly, following the tapestry that hid the secret passage to a chamber upstairs~ non-scented goods…

Leather products did not smell particularly good in their raw state. This was due to the tanning process. Tanning de facto involved less than pleasant smells (mainly urinous, used to make hides pliable) and tradition in many countries was to further aromatize the end product with fragrant essences to hide the manufacturing process off notes: In Italy they used musk, civet and orris butter introduced by Muzio Frangipani (hence "gants frangipani"), in Spain camphor and ambergris, in France orange blossom, violet, iris and musk were the usual essences prefered. It is worthy of mention that it is hypothesized that it is exactly this re-odorized smell that accounts for our perception of what leather smells like, in both sartorial and perfume terms.

Catherine, proud of her beautiful hands and a fan of opera gloves to keep them soft, in her desire to mask the smell of cured leather, liked her leathery garments to be scented with agreeable essences. There was also another reason behind the habit though: the dire need to bring something scented to the nose when crossing the streets of the times, which were in actual fact open sewers transporting human and animal waste to the rivers and ultimately to the sea. The improvement on sanitation in the following centuries was a welcome relief that diminished the need, but the tradition remained, having given European perfumery its kick-start.

Soon indigenous plants, such as lavender, Cassie, myrtle and lentisque (mastic) as well as those that took well to the mild climate (such as jasmine, rosa centifolia and Italian tuberose) started to be cultured for the expressed purpose of using them for harvesting their aroma. Grasse therefore gave priority to the scented part of the industry, while Montpellier remained more focused on tannery per se.

However when in the 1760s the French government raised taxes on hides considerably, the gantiers parfumers suffered a crush to their revenues; especially those of Montpellier naturally. Thus Grasse managed to outdo her rival, retaining the privilege of perfume capital for centuries to follow.

Even today the noble practice of scenting leather is echoed in the niche brand Maître Parfumeur et Gantier, created by the perfumer Jean Laporte, previously founder of L’artisan Parfumer. To this day, mr.Laporte sells scented gloves in his Paris boutique, fusing past and present into one fragrant stanza. The legacy of scented leathers has trully enriched our appreciation of fragrance.

Next instalment will focus on another aspect of leather in perfumery.

.jpg)

.jpg)