The aristocratic aura they exuded makes them the decadent assortiment that a modern woman can reappreciate with eyes anew, cut off from their luxuriant aspirations and focusing on the richness and muskiness of their juice. But the creation process hasn’t been easy. Drom fragrances perfumer Pierre-Constantin Gueros is the son of a Parisian furrier, struggling to come to terms with how to translate his memories into scent: “The smell of the factory and smell of the different leathers and fur—that’s really something I think I will remember all my life,” he says. “And when I say leather, I mean there are so many different leathers. Sometimes I’m frustrated because we don’t have the raw materials to translate this leathery aspect. It’s sensual, but not really animalic. It’s textural—like silk, like wool. It’s very difficult to translate that into perfumes. You have the smell in your head, but translating it is very complicated.” [1] Fur in itself is a material which holds fragrance extremely well (although it’s strongly discouraged by the best furriers in the field to protect the pelts), often for generations which manage to make a simple hand-me-down the object of adoration and an infinite memory capsule.

The aristocratic aura they exuded makes them the decadent assortiment that a modern woman can reappreciate with eyes anew, cut off from their luxuriant aspirations and focusing on the richness and muskiness of their juice. But the creation process hasn’t been easy. Drom fragrances perfumer Pierre-Constantin Gueros is the son of a Parisian furrier, struggling to come to terms with how to translate his memories into scent: “The smell of the factory and smell of the different leathers and fur—that’s really something I think I will remember all my life,” he says. “And when I say leather, I mean there are so many different leathers. Sometimes I’m frustrated because we don’t have the raw materials to translate this leathery aspect. It’s sensual, but not really animalic. It’s textural—like silk, like wool. It’s very difficult to translate that into perfumes. You have the smell in your head, but translating it is very complicated.” [1] Fur in itself is a material which holds fragrance extremely well (although it’s strongly discouraged by the best furriers in the field to protect the pelts), often for generations which manage to make a simple hand-me-down the object of adoration and an infinite memory capsule. Some of the old creators had no special qualms and went along on instinct. Jeanne Lanvin, the classic milliner most famous for her enduring Arpège, was responsible for commitioning in 1924 a rare marvel that was alas discontinued in 1988; a perfume eminently suitable to and evocative of vintage fur wearing. My Sin (Mon Péché in French), a sensuous, unapologetic beauty was created by André Fraysse of Firmenich in collaboration with the mysterious Madame Zed, an obscure personage of Russian extraction that remains a mystery in the history of perfumery. Supposedly resulting after no less than 17 unsuccessful perfumes [2] from her laboratory in Nanterre, My Sin proved that a sinful name and a classy, yet daring smell, was all it was required in the roaring Twenties.Its synergy of heliotrope and aldehydes gives a powderiness that is simpatico to both the romantic floral heart and the animalic musky-woody base of musk, civet and sandalwood, conspiring in giving an aura of silent but powerful distinction.

Some of the old creators had no special qualms and went along on instinct. Jeanne Lanvin, the classic milliner most famous for her enduring Arpège, was responsible for commitioning in 1924 a rare marvel that was alas discontinued in 1988; a perfume eminently suitable to and evocative of vintage fur wearing. My Sin (Mon Péché in French), a sensuous, unapologetic beauty was created by André Fraysse of Firmenich in collaboration with the mysterious Madame Zed, an obscure personage of Russian extraction that remains a mystery in the history of perfumery. Supposedly resulting after no less than 17 unsuccessful perfumes [2] from her laboratory in Nanterre, My Sin proved that a sinful name and a classy, yet daring smell, was all it was required in the roaring Twenties.Its synergy of heliotrope and aldehydes gives a powderiness that is simpatico to both the romantic floral heart and the animalic musky-woody base of musk, civet and sandalwood, conspiring in giving an aura of silent but powerful distinction.However Parfums Weil is the most characteristic example of fur perfumes, being the perfumery offshoot of Parisien furrier, Les Fourrures Weil (Weil Furs), established in 1927. Furriers since 1912, well before they became purveyors of fine fragrance, the venture of the founder Alfred and his brothers Marcel and Jacques into perfume resulted from the direct request of a client for a fragrance suitable to fur wearing. Weil obligingly capitulated to the request and produced scents that would guarantee not to harm the fur itself, yet mask the unwelcome musty tonality that fur coats can accumulate after a while. The names are quite literal: Zibeline (sable), Ermine (hermine), Chinchila, Une Fleur pour Fourrure (A Flower for Furs)...

.jpg) The very first of those was an expansive floral chypre, conveived as an evocation of the oak forests and steppes of imperial Russia and appropriately named after the animal there captured: Zibeline, the highest quality in furs for its legendary silky touch, its scarcity value and light weight. Zibeline belonged to the original fragrant trio line-up that launched the business of Perfumes Weil. Introduced in 1928, Zibeline was comissioned by Marcel Weil and composed by Claude Fraysee assisted by his perfumer daughter, Jacqueline. (The Fraysee clan is famous for working in perfumery: His two sons, André and Hybert were to work with Lanvin and Synarome respectively and the son of André, Richard, is today head perfumer at parfums Caron)

The very first of those was an expansive floral chypre, conveived as an evocation of the oak forests and steppes of imperial Russia and appropriately named after the animal there captured: Zibeline, the highest quality in furs for its legendary silky touch, its scarcity value and light weight. Zibeline belonged to the original fragrant trio line-up that launched the business of Perfumes Weil. Introduced in 1928, Zibeline was comissioned by Marcel Weil and composed by Claude Fraysee assisted by his perfumer daughter, Jacqueline. (The Fraysee clan is famous for working in perfumery: His two sons, André and Hybert were to work with Lanvin and Synarome respectively and the son of André, Richard, is today head perfumer at parfums Caron)Zibeline was released in Eau de Toilette in 1930 but the formulations came and went with subtle differences and their history is quite interesting. First there was Zibeline, then the company issued Secret de Venus bath and body oils product line which incorporated Zibeline among their other fragrances (a line most popular in the US) while later they reverted to plain Zibeline again. The Eau versions of Secret de Venus Zibeline are lighter, with less density while the bath/body oil form approximates the spicy-musky tonalities of the Zibeline extrait de parfum, with the latter being more animalistic. The older versions of parfum were indeed buttery and very skanky, deliciously civet-laden with the fruit and floral elements more of an afterthought and around the 1950s the batches gained an incredible spicy touch to exalt that quality. Later versions of Zibeline from the 70s and 80s attained a more powdery orange blossom honeyness backed up by fruit coupled with the kiss of tonka and sandalwood, only hinting at the muskiness that was so prevalent in previous incarnations, thus resulting in a nostalgic memento of a bygone epoch that seems tamer than it had actually been.

Marcel Weil's death in 1933 did not stop expanding their perfumery endeavours; they added several other perfumes: Bambou, Cassandra and Noir.The Weil family was forced out of France by Hitler, so they re-established themselves in New York from where one of the first perfumes released was Zibeline with the quite different in character chypré Antilope being issued in 1945, upon return to Paris in 1946 when they also introduced Padisha. Sadly the multiple changing of hands resulted in the languishing of the firm by the 1980s and although the brand Weil has been in ownership of Interparfums (Aroli Aromes Ligeriens) since 2002 Parfums Weil is largely unsung and long due for a resurgence.

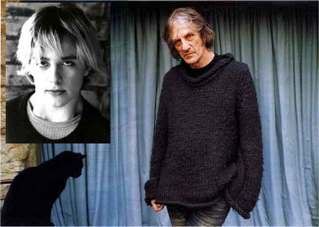

.jpg) The smooth dark fur of a living animal –for a change- was the inspiration behind one of the most elusive vintage fragrances: Mouche by Rochas from 1947, created by none other than Edmond Roudnitska who worked for several of the Rochas thoroughbreds (Femme, Moustache, Rose, Mouselline). Marcel Rochas had a cat, named Mouche, which means “fly” in French and the idea to name a fragrance after his cat was both fun and original.

The smooth dark fur of a living animal –for a change- was the inspiration behind one of the most elusive vintage fragrances: Mouche by Rochas from 1947, created by none other than Edmond Roudnitska who worked for several of the Rochas thoroughbreds (Femme, Moustache, Rose, Mouselline). Marcel Rochas had a cat, named Mouche, which means “fly” in French and the idea to name a fragrance after his cat was both fun and original. .jpg)

The scent came in the same amphora bottle shape as Rochas’ first creation, Femme, designed by Marc Lalique, but with the outer box with the lacy interlay shaded in turquoise rather than grey. Unfortunately Mouche was all too briefly on the scene: It got discontinued in 1962 and remains a rare collectible.

Lots of other perfumes have been linked to the opulence of fur from lynx, ermine and chinchilla to otter, shearling and karakul. Some of the most characteristic is the demi-chypre/demi-floral 1000 by Patou whose refinement, disconcerting and mysterious complexity render it a difficult but intriguing proposition; or the old version of Piguet’s Baghari, which was quite different and more daring than the more demure aldehydic re-issued. Or think of the words of actress and model Camilla Rutherford reminiscing of her mother: “My mother used to wear fur. Her scent was Cabotine by Gres, and sometimes First by Van Cleef & Arpels, and it would cling to her coat. I remember when she was going out, my sister and I would be pawing her because of the softness of her mink and the scents that came from it.” [3]

But even the most unlikely fragrances can have the most surrealistic connotations implicating fur and its mystique. In one such case of free association, Diorella has been linked to “a new fur coat that has been rubbed with a very creamy mint toothpaste. Not gel. Paste.” [4]

Nor are modern fragrances excluded from this wonderful game of synesthesia between touch and smell, between silkiness and swooning. Dzing! composed by Olivia Giacobetti for L’artisan Parfumeur, encapsulates the circus in a bottle with its odours of the great cats, the sawdust in the ring, the leather whip and the cardboard partitions; a wonder which would evoke soft fur even in the absence of it and the perfect accompaniment of a man or a woman on a crisp morning. Muscs Koublaï Khän by Serge Lutens has a silky radiance, warm with the intensity of living beings effortlessly appointed the quintessential parfum fourrure for modern explorers into the terrain of carnal pleasures. And Miller Harris composed L’air de Rien for Jane Birkin (and all of us eventually, as attested by our opinions) to evoke her brother’s hair and her father's pipe, resulting in an animalistic, fantastically ripe and alluring oakmoss and musks blend that would have Guerlain wishing they had come up with such an avant-garde yet also strangely retro composition.

Nor are modern fragrances excluded from this wonderful game of synesthesia between touch and smell, between silkiness and swooning. Dzing! composed by Olivia Giacobetti for L’artisan Parfumeur, encapsulates the circus in a bottle with its odours of the great cats, the sawdust in the ring, the leather whip and the cardboard partitions; a wonder which would evoke soft fur even in the absence of it and the perfect accompaniment of a man or a woman on a crisp morning. Muscs Koublaï Khän by Serge Lutens has a silky radiance, warm with the intensity of living beings effortlessly appointed the quintessential parfum fourrure for modern explorers into the terrain of carnal pleasures. And Miller Harris composed L’air de Rien for Jane Birkin (and all of us eventually, as attested by our opinions) to evoke her brother’s hair and her father's pipe, resulting in an animalistic, fantastically ripe and alluring oakmoss and musks blend that would have Guerlain wishing they had come up with such an avant-garde yet also strangely retro composition.Fur perfumes will continue to hold their fascination for every perfume lover who has been leafing through sepia-tinged old photos with a sigh of unuttered contemplation.

Related reading on Perfume Shrine: Perfume and Furs part 1

[2]Between 1924-1925, the house of Lanvin House launched NIV NAL, IRISE, KARA - DJENOUN (commemorating an Egyptian journey ), LE SILLON, Apres Sport (all of those were discontinued in 1926), CHYPRE, COMME-CI COMME-CA, LAJEA, J'EN RAFFOLE, LA DOGARESSE, OU FLEURIT L’ORANGER (discontinued in 1940), GERANIUM D’ESPAGNE (discontinued in 1962), friction JEANNE LANVIN, CROSS-COUNTRY, and MON PECHE/MY SIN (discontinued in 1988). (source: Tout en Parfum)

[3]Interview in the Dailymail.co.uk

[4]The Face Aug.2005

Vincent Price and Coral Browne photo by Helmut Newton. My Sin and Mouche ads through Ebay. Mouche bottle via Musee de Grasse. Zibeline bottle pic via cyberattic.com

.jpg)